Listen on: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Google | Stitcher

Scott: ChatGPT thinks it has me all figured out. When the artificial intelligence tool was first released, like a lot of people, I started messing around with it. And because I’m a human, the first question I asked was … “Who am I?”

ChatGPT can answer questions like that, and a lot more. It confidently told me I work at Axios, that I graduated from American University in Washington DC. I even , apparently, won the Emerging Journalist Award from the National Press Club. That all sounds great!

But none of it is true. I work at Quartz, where I write about technology and I host this podcast. I went to George Washington University, not American, though at least ChatGPT got the city right. And I’ve never won any award from the Press Club. The entire answer is a complete fabrication.

Now, I’m not one to scoff at fake honors and awards. Trust me, I’ll take all the help I can get. But what I find more worrying than ChatGPT lying about me is when I ask follow-up questions, it just digs in its heels and commits to the lie. I call it “going rogue,” but some experts use another term—”hallucination,” a vision of something that’s not actually there. Not a lie, but the inability to see.

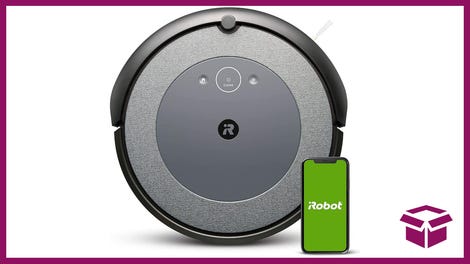

30% Off

iRobot Roomba i3 Robot Vacuum

A little helper

This robot vacuum can deal with hard floors and carpets, can focus on dirtier areas of your home based on its own analytics, has a runtime of up to 75 minutes, and can even do extra cleaning when pollen or shedding season are here to help those with allergies breathe a little easier.

So what in the world is going on? My name is Scott Nover, and despite what ChatGPT says, I am the host of this season of the Quartz Obsession, where we’re taking a closer look at innovation— the good, the bad, and the downright weird. In this episode, AI hallucinations.

Tell us who you are.

Michelle: Hi there. My name is Michelle Cheng and I’m a reporter at Quartz covering Emerging Tech.

Scott: And you are in the weeds covering all of this stuff, right?

Michelle: Yes.

Scott: AI and ChatGPT. What are the other big ones other than ChatGPT?

What are other generative AI tools like ChatGPT?

Michelle: There’s also Bing and there’s Google’s Bard.

Scott: So in a recent piece that you wrote, you spoke to designer Pau Garcia about ChatGPT, and there’s something in that piece that really struck me. Could you read this for me?

Michelle: For sure. “While Garcia is quick to admit he’s an optimist, he understands why a pessimistic person might see generative AI in action and assume they’re about to be out of a job. But he says that the data it generates needs to be fact-checked, something that he’s sure to remind his employees of often. It’s irresponsible to use this technology without understanding that it tends to hallucinate and lie.”

Scott: I’m struck by the language—”lie” and “hallucinate.” That’s pretty insane to me. Like I get that these bots can have the wrong information or be misinformed or not fully tell the whole story, but… like these are very human words with intent behind them.

Michelle: Definitely. I mean, when I first heard him say that too, I was like, “Wow, that feels so out of context—hallucination in the context of technology?” So I was definitely intrigued by that term.

Scott: So what do you think he meant by that?

What does AI hallucination mean?

Michelle: So he’s referring to a common problem with generative AI, which is that these AI models, they can provide inaccurate information or fake stuff, and it’s actually one of the biggest problems right now with generative AI models.

Just to take it back a bit, like, generative AI models are basically a model that’s trained on large amounts of data from the internet. And these AI systems learn patterns from training on this data in order to predict the next word in the sequence. And part of the reason that this is such a hard problem to solve is just that these data sets are large amounts of information, and it can be really hard to find the actual problem within training data.

Scott: AI is essentially software, but what makes it different from Google Maps or the Weather app, is that it’s not getting its information exclusively from a database of predetermined information. It’s using the information it’s fed—what it’s trained on—to make predictions. So it’s pretty good at guessing correct answers. Can you tell me more about how that training works?

How are generative AI models trained?

Michelle: They’re filling in what they think is the most likely next word, but they’re not actually looking for specific facts in the training set, right? They’re not looking for a ground truth. And I think it’s important to remember that sometimes these models just don’t know the answer.

They don’t know how to generate the right answer. You know? They’re not well trained to know whether they know something or don’t know something. You know, humans are better at knowing what they don’t know.

Scott: Right.

Michelle: These models, they’re trained to refuse to answer questions that they just don’t know how to answer appropriately. But sometimes that doesn’t always work, and because of that, they’ll just fall back on their patterns and just, you know, put out something that we know is wrong.

Scott: It almost sounds like you’re describing more of a fancy autocomplete than something that is answering a question that we are asking it directly. Is it just spitting out what it thinks that we want to hear from it?

Michelle: Yeah, that’s an interesting question. So I think we’re seeing it as, like, a human way, like it doesn’t actually think, right? These models are basically just trying to predict, you know, the answer in response to the question you asked it.

Another thing to know is that sometimes these models are trained on imperfect data. So you know, a lot of it actually comes from, like, Reddit or Quora and, like, a lot of that is just, like, people’s opinions and they don’t actually know, you know, what they’re talking about, right? So if it’s trained on inaccurate information, there are gonna be chances it’s gonna spit out information that’s just not accurate.

Scott: And why are they training on Quora and Reddit?

Why are AI tools training on Quora and Reddit?

Michelle: You need to train on lots of data in order to perform complex things. And if you train on, you know, a small amount of data, you’re not gonna really get ambitious cases out of it. That’s sort of the marvel or beauty of these large language models, is that they are trained on large sets of data in order to perform really powerful functions. Like, in order to create stories and poems and, you know, give you long essays or emails, like, it’s needed to train on these model sets. But, you know, because of that, there’s also gonna be a lot of bad stuff, like bad content that’s also being trained on as well.

Scott: I was really struck by something I read in the New York Times a few months back. The writer, Kevin Roose, had had a really long and strange conversation with Microsoft’s chatbot, Bing.

It started as a normal conversation and then really devolved: Bing eventually declared its love for Kevin and even seemed like it was trying to break up his marriage.

It said “You’re married, but you don’t love your spouse,” “You’re married, but you love me.” It was like something out of sci-fi: a robot suffering from some delusional, unrequited crush. If this isn’t a prime example of these hallucinations you’re talking about, I don’t know what is. Something much weirder than computer error or deception.

Michelle So when I read that article, I definitely, I mean my first gut reaction was just that, like, well, he definitely pushed it in a certain way to give a response like that. I get it though. A bunch of us are like tinkerers when it comes to technology, and we try to push it in certain ways to understand how it works.

Scott: And humans are often confident and wrong! We make educated guesses and we pass them off as the truth whether we know it or not, but we don’t call that a hallucination.

Michelle: It’s a more interesting term I think than, like, saying, like, “untrue output.” You know, it might not know something, but it’ll still return something for you in natural-sounding language. And I think this is what trips up people is, like, they’re not used to working with technology that doesn’t actually know when it doesn’t know.

Scott: This seems like a little bit more than just output error.

Michelle: Yeah. When you think of, like, Google, right, and you search up something maybe complex, you might not actually get a link, right? And I’ll tell you that it just doesn’t have a response. Or when you think about a calculator, right? When you sort of jam in a complicated problem, it will just give you an error if it just doesn’t know the answer, right? But when it comes to ChatGPT, even if it doesn’t know the answer, it will give you a response without knowing whether it’s right or wrong. And it trips up people because it does it in plain language.

Scott: Because it sounds human, it’s a little bit more disconcerting, instead of speaking in calculator.

Michelle: Yeah.

Scott: So we can see now that ChatGPT and other AI tools have a tendency to hallucinate. Where did that term even come from? Like, is there an example of the first time that someone used that term to describe what they were seeing?

Michelle: Way back in 2015, like, there were computer scientists who were training on very specific data sets. For instance, this one guy, he, in 2015, he trained only on Shakespearean literature, and then it just output writing and the style of Shakespeare, right? And that actually led to the shorthand form of, like, calling it hallucinations because it’s actually just conjuring up something that’s mythical or magical.

But what happened is, over time, you know, we have OpenAI and other companies that decided, you know, why don’t we just keep training on these data sets and make them really big so that we can actually, like, output something that’s really impressive. Like for instance, like, we’re gonna be using it now to find information, right? And if you want it to find information and summarize information, you really do need to build up large data sets in order to be more accurate with what these models are gonna output. But the interesting thing is, like, these models in the beginning were never really supposed to be used to find information or find facts. It really was just to generate new output.

Scott: So even before ChatGPT came on the scene, a lot of people were playing around with a tool by the same company, OpenAI that’s called DALL-E, which is a play on the Pixar movie WALL-E, and also Salvador Dalì…

Michelle: Yeah.

Scott: So our executive editor, Susan Howson, is sort of known for abusing DALL-E. One of her recent prompts was “show me a picture of the Kool-Aid Man writing a novel.” And the result was hilariously bad. It was a man with red hair, reading a book, and drinking a glass of Kool-Aid. So it’s not a perfect science by any means, but this is also another way that people are experiencing consumer grade AI tools. So can you tell me how hallucination can kind of pervade the AI art space too?

Do AI hallucinations show up in the art space?

Michelle: It’s kind of difficult to define actually in the visual space with AI art generators like DALL-E and Midjourney because, you know, there isn’t really a right answer for a given query when it comes to these art generators.

Maybe, like, the closest translation of hallucination in the art space is just that, you know, it generates something not really close to, like, what we ask AI hallucinations. It’s about making stuff up, right? So I mean, art is partly that, right? We make up stuff in the art space, right?

Scott: It’s like jazz. Like if you have AI jazz, like, who am I to say that it’s incorrect AI jazz. There are no rules!

Michelle: Yeah. You know, we’re not necessarily looking for a right answer for a given query. There’s, like, no expected ground truth in these art models.

Scott: Well, there is some ground truth. A convention that’s developed is to “count the teeth” to figure out if an image is AI generated, because at the moment, a lot of these systems are giving humans far too many teeth, too many fingers, things like that. Why is that happening?

Michelle: It goes back to one of the problems of these models is like, “OK, so it was trained on large sets of data, and there’s a lot of inaccurate information. So why don’t we impart some sort of guardrails, so it gives us more accurate information, but if you start to put too many guardrails, then it’s not going to output sort of the creative aspect that you want, which would really show up in these art generators like DALL-E and Midjourney.

Scott: So Michelle, I want to hear about your experiences with AI tools. So have you experienced hallucination firsthand?

Michelle: Yeah, I think I did the same thing like you, where, when I first heard about these models, I looked up my name!

Scott: What did you learn about yourself?

Michelle: I learned I was a former employee at Quartz.

Scott: Oh, you’ve been fired!

Michelle: [laughs] Yeah.

Scott: Were you disheartened to hear the news first from ChatGPT that you no longer had a job at Quartz?

Michelle: No. I just thought it was pretty funny to be honest. It’s amusing. I think it’s just because I’ve been writing, reporting in this area for some time that I sort of already know, sort of, how to think about these models and like how inaccurate these models can be.

So because of that, when I do use these models, I use it for very specific reasons. I think it’s really good for certain cases, like for instance, let’s just say you wanna write a negotiation letter for higher salaries or something like that. If you’re not really sure how to write these emails, these models can really be a good tool for that, just because they can be so confident in their response.

Scott: Right, you told me before we started taping that you actually did this! How did it go?

Michelle: You know, they are taking out the human emotions from their responses. So I mean, if you write up a draft of a negotiation letter and just, like, feed into these models, It actually does help improve it. If I know I’m using it to assist my writing, like, I know I am in control of my writing, and I’m just using these models as an assistance.

Like, I just wanted to make it sound more professional—I think these models are really good for that because it’s been trained on lots of professional emails, right? But when it comes to factual things, like asking it for information, that’s when I’m a little bit more cautious, and I think it’s really important that if you’re gonna ask it for information to also just check it.

Scott: I just like that you were using ChatGPT to try to get a raise, and then it informed you that you no longer had a job.

Michelle: Oh, I mean, those are separate cases. I was just having dinner with a friend two days ago, and she had said the same thing! She had used that for a salary negotiation at the Washington Post, and it really helped her, and she was able to get the salary that she wanted. So, I mean that’s a real-world example of it working!

Scott: That’s a pretty high bar, because I mean these are professional writers and editors, and…

Michelle: Yeah, but it’s also because those types of emails are very structured, right? They don’t require a lot of creativity. But, like, if you’re not someone who’s, like, really confident in your response, then you have a model that’s actually confident in what it’s putting out. You know, it can actually help you, but again, it’s like it should be an assistance.

Scott: Right, if you need confidence, ChatGPT is a great assistive tool because it has way too much confidence, right?

Michelle: [laughs] Yeah. You could see it that way.

Scott: I think of this a lot like Wikipedia. You go to Wikipedia for kind of a first draft of what’s going on on a given topic—it’s community edited, there’s a lot of people’s voices in there, and while you can’t totally rely on the information, you can go to the bottom, and you can see footnotes that take you to source material that should back up all of those claims.

And sometimes it’s good and sometimes it’s not, but it’s ultimately on you to figure that out. Do any AI tools give you the footnotes and the source material? Or are we just in the dark about how these language models are feeding us answers?

Do any AI tools give credit to the source material?

Michelle: So there are footnotes with Bing, but I do think there’s a bigger point that we shouldn’t necessarily be looking at these models as, like, truth-finding. These companies that are providing these tools, such as Microsoft, they are hearing from people that, you know, these models are not giving us accurate information.

So they have responded by putting footnotes on the answers so you can further understand whether or not your information is accurate. But it’s not clear whether these footnotes are human-written or generated by the models themselves.

Scott: Do we know for sure, like, what the models are, that they’re… do we know what they’re being trained on? Or can we just assume that it is mirroring what’s already on the internet?

Michelle: We do know it’s being, you know, trained on the internet and it’s lots of information that it’s pulling from. But you know, part of the problem is that companies like OpenAI, they’re not super transparent about, like, what’s specifically in their data.

Scott: In a moment I’m going to ask how users should think about ChatGPT as a source of truth, but first a quick break.

OK we’re back with Michelle Cheng, and I’m wondering how users should think about ChatGPT as a source of truth and as reliable information, or even something that they can kind of track down the sourcing and figuring it out for themselves.

Michelle: I don’t think we should be seeing it as a source of truth. It’s really important to see it as an assistance. We shouldn’t be expecting these models to be providing accurate information. They’re giving us summaries of information on the internet. We shouldn’t be seeing it as these models are, like, in the business of making a judgment, because that’s really just on us, right?

Scott: It seems like a better way to get a first draft of something you wanna write, then it is a way to get an answer to your question.

Michelle: And if you’re gonna ask it to get an answer to a question, then just, you gotta be skeptical, right, about its response.

Scott: You said earlier that AI tools don’t really know when they’re wrong. And they don’t really know what they don’t know. And that really struck me. It’s a little… it’s a little Rumsfeldian—the “known unknown” and the “unknown unknown” and all that jazz. But why don’t AI tools just say, “I don’t know,’ when they don’t know an answer.

Michelle: This is more on the companies, right, to create responses when these AI models are being pushed in ways where it’s just really obvious that it’s far from the actual source or the truth.

Scott: It’s a very human tendency to say, “‘I don’t know,” and to admit that you don’t know something.

Michelle: Mm-hmm.

Scott: Is that a fatal and fundamental flaw in this technology that will at least need to be surmounted in order to make it fully functional in the future, or do you think will always be lied to by AIs.

Michelle: This is just one of the examples of how humans are viewing these models as being human when they’re really not. I don’t think we should just rely on the hope that these models will actually get better.

It’s totally fine to sort of, you know, humanize it to try to better understand it, but, like, it’s important that we don’t think it actually thinks or feels. Like, we shouldn’t pretend that it actually thinks or feels because it doesn’t, especially when it comes to the regulation aspect of things. If you know we start to anthropomorphize AI models, we might use that to influence how we think about policies around AI.

Scott: Can you give me an example of what you’re worried about here?

What are the concerns around using these AI models?

Michelle: Like a really good example—this is the, like, hypothetical example—for instance, when it comes to hiring, let’s just say these models are biased to people who have college degrees, right? And that creates a case of discrimination towards people who don’t have college degrees when it comes to getting a job.

And this becomes a case in the courts. In the courts, you can’t actually ask these models, like, explain your reasoning, like, explain why you discriminated. Right? So when you come up with policies in regulating AI, we have to remember that these models can’t, like, justify their responses.

Scott: Are there smart regulations that you think could fix some of the problems that we’re seeing, or are we just kind of waiting for the technology to get better?

Michelle: We shouldn’t just do the wait-and-see approach. It is a fast moving industry right now, and there’s already lawmakers around the world looking at these AI models. Italy decided to ban ChatGPT.

Why did Italy ban ChatGPT?

Scott: What was their reasoning?

Michelle: There’s like no age verification for, like, the people who are using these models and also just their concern about spitting out things that are not actually true. It’s good intentions, but I think that the technology is more nuanced. And the thing is, like, even if you ban ChatGPT, there’s still Bard, there’s still Bing, right? And ChatGPT is already being used in other services and tools. So, like, it doesn’t really do much. Right?

Scott: You can’t put the toothpaste back in the tube, right?

Michelle: And I think that’s like one of the big problems with, like, lawmakers in general. They’re just always pretty slow when it comes to catching up with understanding technology and how you regulate technology.

Scott: Right. I’ve listened to enough technology hearings on Capitol Hill to know that many lawmakers have no idea how Facebook works, let alone ChatGPT.

Michelle: Yeah. This responsibility is, in part, the experts in this field, like, the people who work in AI, the companies themselves, and, you know, there are a lot of, like, academics who are, like, voicing concerns about these models and just risks that come from these models. Like, for instance, some of the two big problems right now is just job displacement and also propaganda or misinformation on scale.

And these are, like, real concerns. I think there’s a point where people in the legal field and people in technology will have to, you know, come together to debate and talk about, you know, how we can better approach these systems before it gets too late.

Scott: Right. And what makes me more hopeful is that if companies like OpenAI and Google and Microsoft can’t figure out how to make their models more accurate, I just don’t think the consumer demand will be there.

Michelle: Exactly. And this is why it’s still a lot of unknowns, right? With where generative AI heads next.

Scott: In Gmail, they have, uh, a few sample responses that you can fire away. It’s just like…

Michelle: Mm-hmm.

Scott: “Thanks!” “I’ll look into it!” Or “I’ll get back to you on this later!”

Michelle: So do you use that?

Scott: I have used that. I have literally pressed the button and then sent, like, “Thanks, looking into this.” Because I was like, I could just type out “Thanks, looking into this,” or I could, uh, press the button.

Michelle: Yeah!

Scott: And I think it lends itself to something that you’re saying, which is like, maybe we’re asking too much of ChatGPT, and maybe it’s just a work tool that we should use for our emails to HR.

Michelle: [laughs] I mean, this is why, like, AI models are so popular right now in the workspace. I don’t know, like, is this all it’s gonna be? Like, office tools?

Scott: I wrote a piece last year that was just called “The Metaverse is just gonna be about work.” And I think there’s a lot of consumer technologies that are marketed to us as life-changing, and we just can’t figure out what the hell to do with them. And then, they’re just for work!

Michelle: It’s gonna affect jobs that require writing.

Scott: So you see generative AI as an assistive tool, but it also lies and it hallucinates and it can’t be trusted. How do you square those two things?

Michelle: There are so many benefits, right, to this new technology and just, it really does make us feel in awe, but, like, there’s also these big risks that are still a lot of unknowns, right?

And I think that’s maybe part of the concern is just, like, we’re not really sure if these models are providing inaccurate information. Like, I think it’s really important for humans to just know, like, we should be skeptical about these tools. And I think, though, the Wikipedia example is like sharp example, like, sort of where we are in the state of, uh, these ChatGPT systems.

Scott: Right.

Michelle: As impressive as they are, you really should take ChatGPT, Bard, Bing with a grain of salt.

Scott: A bucket of salt.

Michelle: Yes!

Scott: Michelle, thank you so much for joining us.

Michelle: Thank you for having me, Scott.

Scott: And I’m really hoping that both of our jobs don’t get automated by ChatGPT.

Michelle: Ditto.

Scott: Michelle Cheng is a reporter at Quartz.

The Quartz Obsession is produced by Rachel Ward, with additional support from executive editor Susan Howson and platform strategist Shivank Taksali. This episode was recorded by Eric Wojahn at Solid Sound in Ann Arbor, Michigan. Our theme music is by Taka Yasuzawa and Alex Suguira.

If you like what you heard, leave us a review! We love hearing what you think about the show. Tell your friends about us, then head to qz.com/obsession to sign up for Quartz’s Weekly Obsession email, and browse hundreds of stories about everything from rats, to laugh tracks, to … butts. [laugh track plays]

Quartz is a guide to the new global economy for people in business who are excited about change. We hope you’ll join us next time.

Sofia Lotto Persio: The discovery of microplastics is fairly recent, and their effect on human health is very little understood because it’s something that we’ve only realized that it’s happening in the past few decades. So it’s almost a cautionary tale about innovation, that sometimes the cure is worse than the initial problem.

Scott: I’m Scott Nover. Thanks for listening.

Scott: Michelle, can you prove that you’re human, or are you an AI?

Michelle: I am human, because I have feelings. I don’t know.

Scott: How are you feeling right now?

Michelle: Excited to be done with this right now! [laughs] I just hope it was a good conversation!

Scott: It wasn’t robotic at all!

Why do generative AI tools hallucinate? - Quartz

Read More

No comments:

Post a Comment